Cultural Heritage

Transport

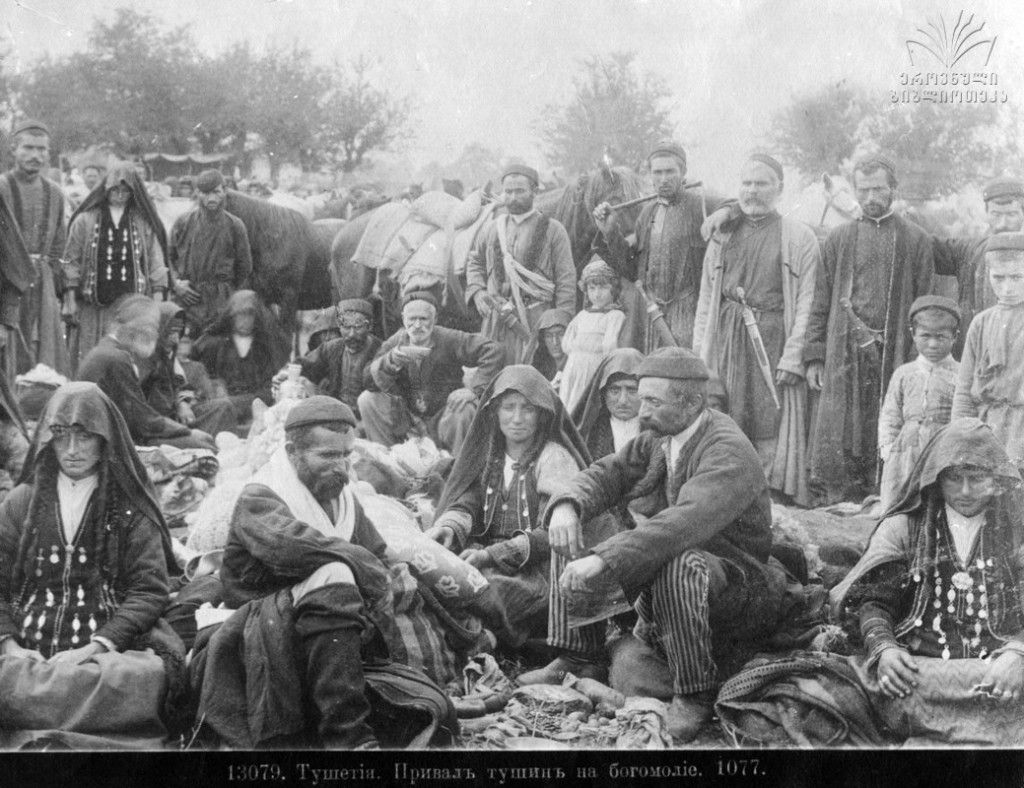

The gathering of Tush weepers began at the beginning of the last century. Consequently, many of their samples have survived. Each of them expresses unspeakable sorrow, pain and respect

Loud weepers

The eternal theme of presence-absence, the relation to death is especially well seen in the mountain folk poetry. Funeral poetry also belongs to it. Pshav-Khevsureti, Tusheti, Mtiuleti-Gudamakari and Khevi are distinguished in this aspect, as the mountain has always been a treasure and repository of true and eternal values.

Funeral poetry is of two types according to its functional purpose - non-canonical and ceremonial. Mixing them is not right. The tradition of mourning the cult of the deceased is celebrated in different parts of Georgia with different cries. There are: loud weeping, crying out loud, bell weeping, call weeping, weeping while counting, etc.

As for general lamentation, in Tusheti it was done according to the age, rank and condition of the deceased. These texts, as in Pshav-Khevsurian, are improvised. It belongs mainly to women. It is significantly different from Pshav-Khevsurian in structure, rhythm, content and form, as it is an irregular 12-line verse, sometimes with 13-14 syllables in a line, but in this case, these extra syllables are chanted in a way to fit 12-syllable melody. There is also a 10-line string, in this case it complements the weeping melody by subtracting or sighing. As in other parts, it was

considered shameful to cry when a small child died.

"walk o mother, walk till dawn,

While scaring the little bull,

The road to enlightenment is far away, almost withdrawn,

I am looking at you, my friend, in full,

I do not know, the rider is better, or the horse,

Just let those boys from Dartlo come down,

On horseback, to the bridle, with no doubts,

Who is now your master, my little son, in town,

Who will make you the new throne for your stallion,

Who will take you in the opposite direction?

Who is making you forget this country of the sun, our companion,

Where are you, my love, where can I send you affection,

With whom are you, on which canyon.

It was also considered a shame for the wife to cry for her husband, and if she still cried for him, in this case, she would apologize:

"I must cry too, as well,

As he is my husband, I am not ashamed, you can tell,

If he wears a hat, you can see, that he is a man,

Or in fight testing him, you also can,

He has better whip and fabric than some of them,

Nabadi and a hat counts as well,

And if you shall die,

I will sit on your grave till dawn, looking up high,

I woke up last night,

I can no longer stay up late during the evening, which is not right,

Come to me, my brother-in-law,

Come to me and give me strength, to forget what I saw"

They especially cried for the man who died without an heir. Occasionally, the weeping verse referred to the deceased's relatives, A.K.A the spirits, who were waiting for in heaven (meaning the mother's brothers or relatives). The focus is mainly on the masculine qualities of the deceased, as in the following weeping verse, which was dedicated to the famous brave man of Chigo:

"You stepped out from a different door, you good man,

You, who is so proud, with words like honey overflowing rom your mouth, that you can,

You flew in this domain like a hawk,

And now, like an eagle, you must leave your nest, without talk"

Cases of weeping for outsiders were not so rare in Tusheti. For example, the Pshav saint who died on a different soil Tusheti was mourned with a weeping verse. If He died in Tusheti,dhis village or community did not know what to say to his relatives. The Tush people rested the shepherd the famous Keedan mother of Shenako weeped for him:

"The leaves are thorny, oh, the one who has been accepted by the wind,

The bull wonders alone, near the Narikala water, searching for his kin,

Oh, how pitiful is the bull, seeking,

With none does he have the privilege of speaking,

My mother, brothers and sisters, they all cry for you,

How are you so deserted, that none of your kin cries, not even a few,

Where do we bury you, outsider, as in this land, you never grew?"

DISCLAIMER:

The translations, obviously, do not show the example of the classic Tush verse, as the mountain dialect cannot be translated into English.

Poem translated by: Lika Sharashidze.